The ECB just confirmed our worst fears.

In its last address, it’s president, Christine Lagarde gave a carefully crafted guidance speech and warned about EVERYTHING we’ve recently predicted.

This means only one thing: the tipping point is near.

Deglobalizing the World

In previous letters, we predicted two game-changing shifts that would rock the global economy to its core.

First and foremost, the dollar that has ruled global trade for the past 70 years will lose its reserve currency hegemony.

I’m not saying the dollar will cease to exist, but it will no longer be the sole currency used for settlements, as it is today.

China is now in the final stages of launching a new reserve currency for the BRICS. And in preparation for that, the BRICS has invited new members to its block.

As we wrote last month, the BRICS nations announced they would entertain allowing other countries to be included in their coalition. And immediately, a dozen oil nations lined up—including oil producers Argentina, Egypt, and Algeria, and even bigger players, such as the UAE, Iran, and even Saudi Arabia.

In other words, we are entering Bretton Woods III—a monetary era where no reserve currency will have exclusive settlement rights.

And that will have vast implications for the U.S.

Key among them is that the U.S. will lose the “exorbitant privilege” of printing as much of its currency without international recourse, and lose the ability to borrow in perpetuity with the same foreign demand it’s had for decades.

What happens to the dollar if the U.S. loses these privileges?

Such a reputational shock will certainly devalue the dollar, as Nixon did after he ended the dollar’s convertibility to gold.

But this shift in global trade goes beyond just settlement.

Our second big prediction was that global trade would fragment along geopolitical fault lines. And that we would witness the biggest onshoring of supply chains since the World Wars.

That fragmentation is already underway.

Exports of food, fertilizers, and energy have been heavily sanctioned since the beginning of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, and now, as we just predicted would happen, China is now threatening to ban the exports of critical rare earths.

Via Nikkei Asia:

“China is considering prohibiting exports of certain rare-earth magnet technology in a move that would counter the U.S.’s advantage in the high-tech arena.

Officials are planning amendments to a technology export restriction list, which was last updated in 2020.”

But this new era of mercantilism isn’t limited to commodities.

It extends to IP and technology, too.

In our recent letter, “A Battlefront for the New World Order,” we exposed how Washington convinced its Western allies to ban chip technology transfer to China.

And they have officially followed through.

Via Politico:

“The Dutch government confirmed for the first time Wednesday it will impose new export controls on microchips manufacturing equipment, bowing to U.S. pressure to block the sale of some of its prized chips printing machines to China.”

Over the past two decades, the world has built the most interconnected trade network ever seen: a “trade block” that transcended geopolitics in pursuit of commerce.

And this globalization has been one of the most deflationary forces of the past decades.

But now this trend has been forced into reverse.

As global trade crumbles, many goods will be hoarded, levied, and otherwise protected at all costs. And their supply chains will become “domesticated” along political borders.

Everything will get more expensive.

ECB Drops Truth Bomb

Last week, ECB president Lagarde flew to New York and warned policymakers of this changing global order. And her talk encompassed so much of what we predicted over the past years.

You can read the full transcript of her speech here.

Here are some key takeaways.

For starters, Lagarde acknowledged that—as I wrote in “A New Reserve Currency Is Live,” China’s economy has grown so powerful it now has what it will take to overthrow the dollar:

“In recent decades China has already increased over 130-fold its bilateral trade in goods with emerging markets and developing economies, with the country also becoming the world’s top exporter.[13] And recent research indicates there is a significant correlation between a country’s trade with China and its holdings of renminbi as reserves.[14] New trade patterns may also lead to new alliances. One study finds that alliances can increase the share of a currency in the partner’s reserve holdings by roughly 30 percentage points.[15]

All this could create an opportunity for certain countries seeking to reduce their dependency on Western payment systems and currency frameworks.”

She also affirmed that the world is moving away from a unipolar trade system. And that free trade will soon fragment around two trade blocs: the West and China’s led BRICS.

“We are witnessing a fragmentation of the global economy into competing blocs, with each bloc trying to pull as much of the rest of the world closer to its respective strategic interests and shared values. And this fragmentation may well coalesce around two blocs led respectively by the two largest economies in the world.”

She even brought up the niche minerals industry that we exposed in “The Next Bellwether Commodity,” as one of the West’s Achilles heels:

“Today the United States is completely dependent on imports for at least 14 critical minerals.[3] And Europe depends on China for 98% of its rare earth supply.[4] Supply disruptions on these fronts could affect critical sectors in the economy.”

And just as we have warned, Lagarde expects a series of destructive supply shocks as the world transitions to this two-sided trade, which, by the ECB’s calculations, can raise inflation by 5% in the short term:

“One recent study based on data since 1900 finds that geopolitical risks led to high inflation, lower economic activity and a fall in international trade.[7] And ECB analysis suggests similar outcomes may be expected for the future. If global value chains fragment along geopolitical lines, the increase in the global level of consumer prices could range between around 5% in the short term…”

And last but not least, she confirmed what we’ve been saying for years: central banks are imminently switching from fiat to CBDCs:

“How central banks navigate the digital era – such as innovating their payment systems and issuing digital currencies – will also be critical for which currencies ultimately rise and fall. This is an important reason why the ECB is exploring in depth how a digital euro could best work if launched.”

It’s one thing to hear these conspiracy-like warnings from us, but when the chief of one of the world’s most important central banks echoes our predictions, it really is time to take notice.

Back to 1970

This “new global map,” as Lagarde calls it, is one of the biggest macro stories in modern history. And while we can’t be certain as to how this will play out, there are historical precedents we can draw from to predict what might come next.

Just look back to the 1970s.

High inflation isn’t the only thing that we have in common today with the 1970s. The root causes of it and the policy responses that followed are also alarmingly identical.

For example, much like today, the inflation of the 1970s was a result of both monetary policy and supply-side shocks.

In 1971, President Nixon breached the Bretton Woods agreement and prohibited the dollar’s mandatory convertibility to gold, resulting in an instant dollar devaluation against other currencies.

On top of that, OPEC’s oil embargo and following tensions in the Arab world brought two oil supply shocks. That resulted in oil prices soaring 6X when adjusted for inflation.

Today, increased energy costs have trickled up, exploding consumer prices.

And what has been the policy response to these inflationary forces?

You guessed it: mercantilism.

Major powers began to adopt protectionist policies to protect domestic industries at the expense of foreign competitors. This included the use of tariffs, import quotas, and other trade barriers.

Via Wall Street Journal:

“In the 1970s, oil-price hikes and other shocks triggered inward-looking, mercantilist policies, including in Europe and the United States. Immediate policy responses were not overly protectionist: There was no equivalent of America’s 1930 Smoot-Hawley tariff. But escalating domestic interventions on both sides of the Atlantic exacerbated economic stress and prolonged stagnation. Not least, they spawned protectionist pressures. Industry after industry, coddled by government subsidies at home, sought protection from foreign competition. The result was the ‘new protectionism’ of the 1970s and 1980s.”

The result was that this protectionism didn’t just make stagflation worse; it made investing a real headache.

Portfolios in the Dump

If you pay close attention to historical asset comparisons, you’ll notice that most use nominal numbers. This can lead to a distorted view because they obscure the actual value of those assets.

This is particularly misleading when dealing with extended periods of inflation, such as those experienced in the 1970s.

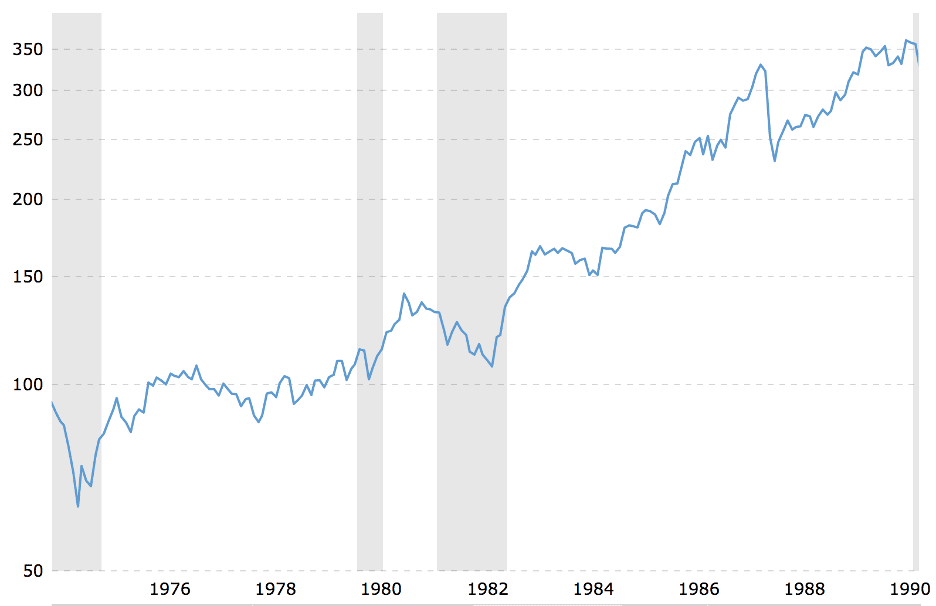

To illustrate this, take a look at the S&P 500’s nominal performance over a period of two decades beginning in 1970:

Based on this chart, it seems that stocks were a safe bet. Not only did they hold out during the ’70s inflation breakout, but by 1990, the S&P 500 even experienced a fourfold increase.

BUT what happens when you adjust these numbers for inflation?

See that chasm in the middle of the chart?

That’s the real value of stocks being eaten away by the inflation of the 1970s. It took the stock market 20+ years to break even on those losses.

In other words, in inflation-adjusted terms, the stock market had lost two decades because of the 1970s.

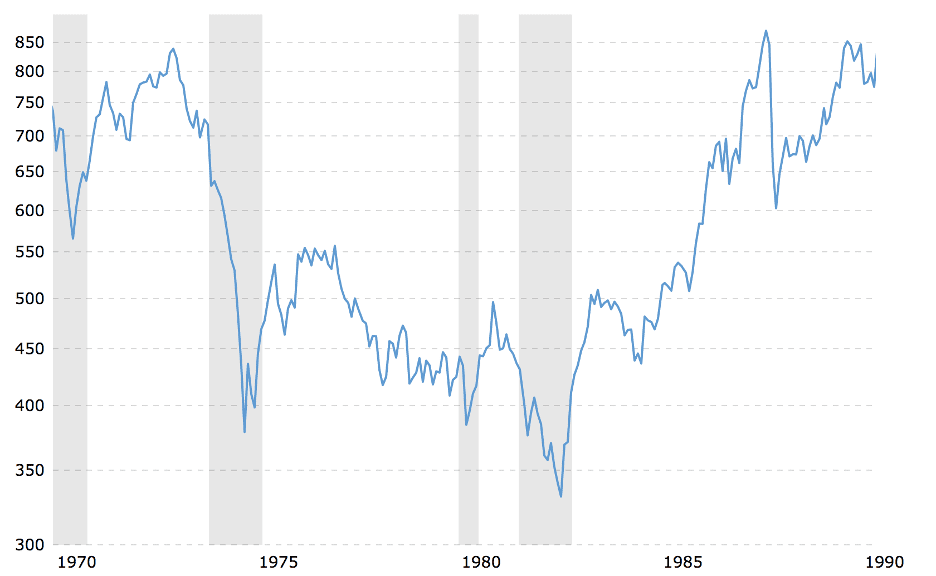

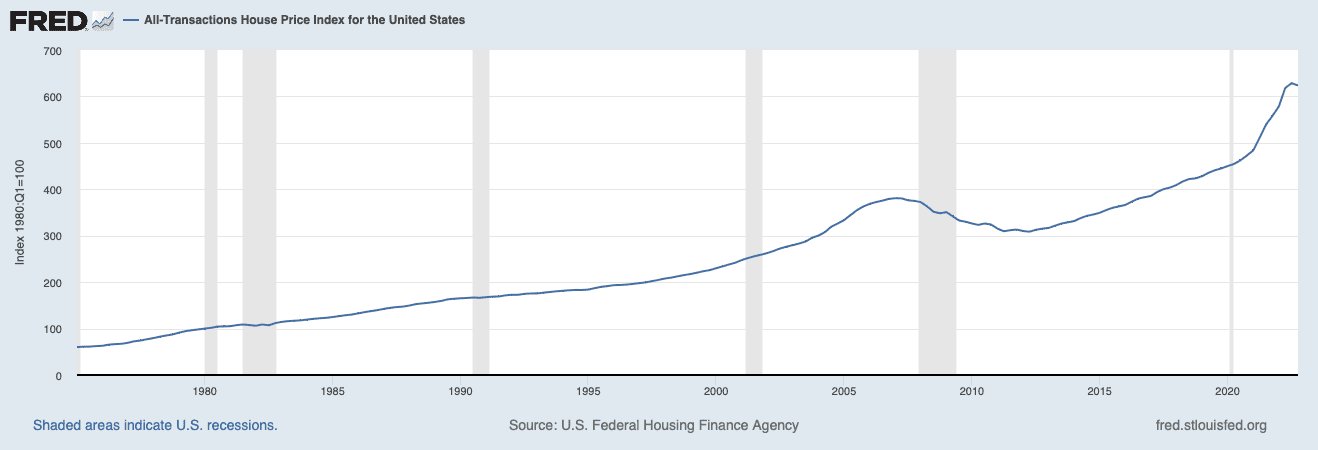

What about real estate—the mainstream inflation hedge?

While some regions did really well during the 1970s, most real estate assets didn’t hold up.

For example, while housing in California tripled in value during that timeframe, housing prices nationally dipped when adjusted for inflation.

Take a look:

The only two asset classes that performed well? Commodities and gold.

Commodity prices* experienced a staggering 8-fold increase during the 1970s, which further skyrocketed to a cumulative gain of 12 times over the subsequent decade.

Even when adjusted for inflation, this asset class handed investors a multi-fold gain.

(*As measured by S&P GSCI Commodity Index, which includes unleveraged, long-only investment in commodity future contracts diversified across a broad range of commodities.)

The same happened with gold.

From 1970 to 1990, gold appreciated 4x in value—in real terms.

These kinds of returns have beat some of the most iconic tech plays over the same timeframe.

Placing Hedges

Considering the proximity of these parallels, we can’t realistically think of a more logical investment playbook moving forward.

In other words, there are two asset classes that should outperform from a historical perspective: commodities and precious metals.

Some would argue that commodities have already had their 15 minutes of fame, and that the easy gains have already been made.

And while we don’t think the run for commodities is over, the other asset class, precious metals, is just warming up.

With the new global order coming our way that Lagarde just confirmed, precious metals’ REAL run-up likely hasn’t even begun.

Seek the truth,

Carlisle Kane

You cannot place stagflation on protectionist measures. When our or any nation was self-sufficient, the concept never appeared. It is only after excessive money printing and the picking of winners and losers in policy that awakens the monster of stagflation. It has been with us for two years. We are in a “stealth” recession, as per Evolution of Democracy blog.

Thanks, I am a Precious Metals Investor, worked in mining 39 year, including U/G, overseas, Saudi Arabia, Africa, Guyana, Philippines. Have Mining Stocks and hold Gold Bullion.

“In other words, we are entering Bretton Woods III—a monetary era where no reserve currency will have exclusive settlement rights.”… and where none of the national currencies have tangible value. How does Central Banker A really know how many dollars, yuan, shekels or lira Central Banker B is surreptitiously cranking out?The mainstream financial press will strain their necks trying to avoid looking at the obvious solution: the reinstitution of hard money. Actually, the gold being hoarded by privately owned central banks will have to be physically pried from their hands by the public when it finally wakes up, to accomplish this, but as Hans Sennholz asked way back in 1975, when the U.S. national debt was under $1 trillion, “When will the world make peace with gold?”