Forget Ebola, Worry About the Coconut Virus

A week ago, I was at a birthday party for a rocker who had just turned 50.

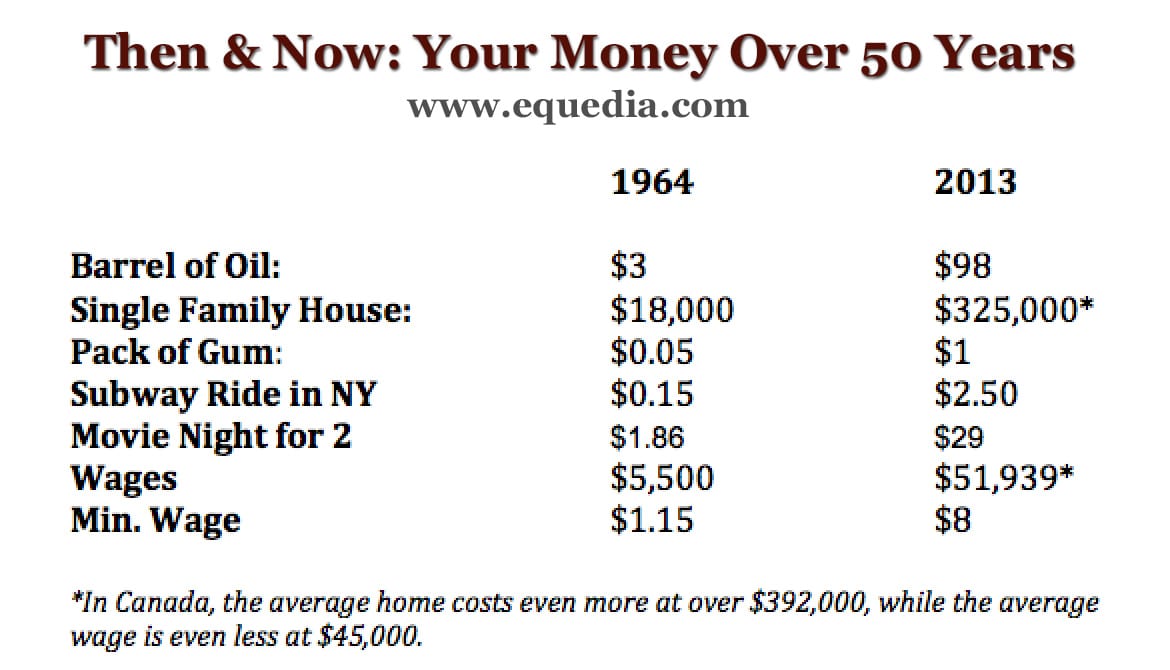

His daughter, my girlfriend’s best friend, had placed notes on the tables showing the cost of things when he was born (1964) and the cost of things today.

I couldn’t help but snicker at what I saw: The drastic difference between the average cost of goods, services, and housing and the average annual salary.

Since the notes were a novelty item, I didn’t know if the prices shown on the notes represented “nominal” or “real” prices. So I asked.

No one knew the answer. As a matter of fact, most people couldn’t tell me what the differences between nominal and real prices were.

I explained.

Nominal prices are the actual sticker price of something, not adjusted for inflation; in other words, a dollar is worth a dollar no matter how you look at it.

Real prices are the prices after it has been adjusted to account for inflation; in other words, what one dollar can actually buy.

That seems simple enough.

But as we discussed the differences further, I soon found out that most didn’t understand the modern concept of inflation.

Sure, they knew inflation meant rising prices.

But they all believed, as they were always taught in school, that inflation was the result of increased aggregate demand that lead to rising prices.

And if they told me that 50 years ago, I would have said they were mostly correct.

But that’s 50 years ago.

Do you remember the prices of goods from when you were a kid?

Brainwash 101

In our modern society, inflation is now being used in place of devaluation.

That’s because the dollar is now backed by nothing more than promises – as it has been since the end of the Bretton Woods System, somewhat backed by gold (see “How the Government Borrows Money”).

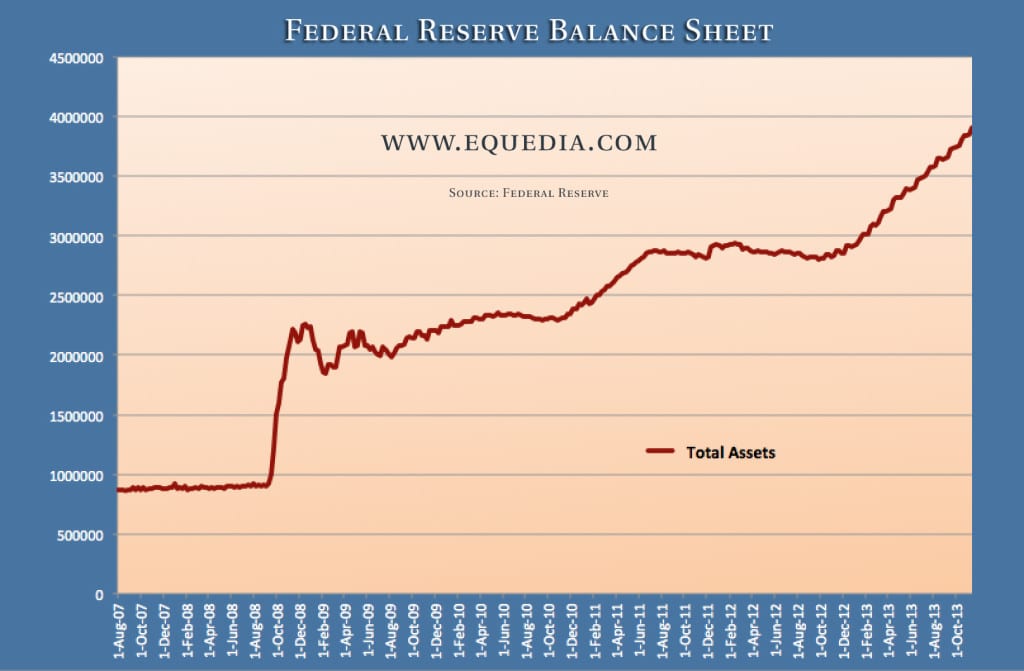

And since the Fed is now the biggest holder of U.S. debt (see Biggest Buyers of Garbage), it also means the dollar is now primarily backed by the Fed’s accounts which have never been publicly audited.

I want to go back to a Letter I wrote last year on inflation, “Inflation vs. Deflation: A Growing Currency War.”

(The Fed) want(s) you to believe that we absolutely need inflation because the opposite – deflation – is a terrible thing. They want you to believe deflation represents a lack of economic growth.

But historically, deflation under normal circumstances has never been the cause of poor growth – as a matter of fact, it was quite the opposite.

Deflation occurred in the U.S. during most of the 19th century (the most important exception was during the Civil War).

But this deflation was caused by technological progress that created significant economic growth.

This was also a period before the establishment of the US Federal Reserve System’s role in active management of monetary matters.

So “they” may tell you that deflation is a very bad thing.

But what deflation really means is a lack of growth in “their” banking system.

The Fed is a bank. Its growth – like all banks – relies on lending.

If people stop borrowing, banks wouldn’t make money.

The more they lend, the bigger they become.

And the Fed has lent more money since 2007 than it ever has in its history.

Here’s a look:

Starting to get the picture?What Inflation Means for the Fed

The Fed’s policy is to prevent inflation from falling too low.

What that really means is that their policy is to prevent the cost of living from…well…staying the same.

Inflation is good for those who are heavily indebted, but punishes those who have been financially responsible.

The scary part is that people have fallen for the “we need inflation” mentality because they have been so heavily brainwashed by the media that inflation is a great thing and deflation is really bad.

Inflation vs. Deflation

Inflation means prices for goods and services are rising, which means you have to pay more for something.

Deflation means the opposite, which means you pay less.

The less we pay, the less likely we need to borrow to pay for the things we buy.

We’re all bargain hunters. If we could buy a new iPad for $500 instead of $1000, we would.

So why then would we want inflation? Why would we want to pay more for something, when we can pay less?

Why wouldn’t we want deflation instead?

Deflation: Good or Bad?

If our society never fell into this debt crisis, we would want deflation.

But since our world has fallen for the idea of cheap money via the central bank system, deflation can be scary.

Deflation increases the real value of debt.

In other words, deflation makes it harder to pay back money that you have borrowed.

Let’s use housing as a simple example.

If housing prices drop by 10% (deflation), a homeowner with a large mortgage could see the real value of his debt rise by 10% because he now owes 10% more than what his home is worth (assuming he borrowed all the money for his house to keep the math simple.)

Since deflation means lower prices, which can eventually lead to wage declines, that same homeowner would now have a higher ratio of monthly mortgage payments to wage income.

Deflation would mean higher loan-to-value ratios for homeowners, leading to increased mortgage defaults (which we saw in 2007) and ultimately a crash in the banking system.

Banks need people to borrow to keep their system alive and they have done a great job of making everyone pay more for everything as a result.

The more expensive things get, the more we have to borrow – and that’s good for the banks.

Housing prices haven’t gone up because the real estate market is hot; they’ve gone up because credit has been cheap.

The next time you’re buying a condo in Vancouver for $1 million, or a condo in Toronto for $750k, don’t thank a great real estate market for that – thank the central banks.

Deflation: The Bigger Picture

Deflation causes a country’s debt-to-GDP ratio to rise.

As prices fall GDP is lowered, which then leads to a country’s inability to service its debt – the same debt accumulated as a result of easy money.

In other words, if deflation occurs, many countries could default…or print more money to prevent that from happening – which is exactly what the US is doing.

The central bankers’ blueprint is very simple: If they can make you believe that inflation is low, then they can print as much money as they want, further entangling the world in a central bank credit system.”

Ludwig von Mises, one of the most notable economists and social philosophers of the twentieth century, defined inflation as the following:

“Inflation, as this term was always used everywhere and especially in this country, means increasing the quantity of money and bank notes in circulation and the quantity of bank deposits subject to check.

But people today use the term ‘inflation’ to refer to the phenomenon that is an inevitable consequence of inflation, that is the tendency of all prices and wage rates to rise. The result of this deplorable confusion is that there is no term left to signify the cause of this rise in prices and wages.

There is no longer any word available to signify the phenomenon that has been, up to now, called inflation.”

Well said.

In simpler words, the term inflation is now widely used simultaneously to describe two very different things: True Price Inflation and Monetary Inflation.

The Truth About Your Money

True Price Inflation is caused by an increase in aggregate demand forcing the price of goods and services to go up. It is what most of us have been taught in Economics 101.

For example, let’s say you’re on an island and there are 1,000 coconuts available (a fixed supply), the price of a coconut will depend on how many people want one. If 5,000 people wanted one, the seller can raise prices so that the richest 1000 are the only ones that can afford to buy one. When demand is higher than supply, prices go higher.

However, monetary inflation – often mistaken for true price inflation – is not the result of aggregate demand, but a decline in the value of a currency.

Let’s again use coconuts as an example.

You start on an island with a limited supply of 1,000 coconuts. So when people trade these coconuts for other things, the price is fairly constant.

Over time, you save up 20 coconuts, which you can trade for a new hut.

Then, one day, a ship hits some rocks by your island, and its cargo of coconuts washes ashore.

Suddenly, 5,000 coconuts are lying on the beach, and everyone scatters to grab some.

Because the coconut supply has increased, your coconuts can no longer be traded for a new hut because every one has more coconuts.

This scenario shows that monetary inflation is not the result of an increase in aggregate demand, but a decrease in the demand of a currency. In the above case, coconuts are the currency.

As I mentioned earlier, in our modern society, inflation is being substituted for another word: devaluation.

Now think of the coconut scenario in the context of our own current financial system, substituting coconuts for dollars.

Every time you save enough coconuts to buy a new hut, the Fed drops another boat of coconuts onto your island.

All of a sudden the coconuts you saved can no longer buy you what they once did before the Fed’s drop.

If you want to buy that hut you have been saving for now, you’ll now have to borrow more coconuts.

The Coconut Virus

The Fed has dropped an unprecedented amount of coconuts onto our island.

But that’s not the worst part.

Along with these coconuts, the Fed has also dropped a coconut virus that spreads to all other coconuts.

We’ll call this virus negative zero real interest rates.

This virus causes coconuts to spoil over time.

So if you save your coconuts, they will eventually become worthless.

But that’s not all.

The Fed will continue dropping these coconuts to make sure you use them before they spoil.

Get the picture?

Back to Real Life

We can’t control how fast these coconuts drop, and we can’t control where they end up.

Let’s also assume there are those who started with more coconuts and used their riches to build a coconut collector, so that every time coconuts were dropped, they would gather the most coconuts.

We’ll call these guys the richest 0.0001%, or bankers – whichever you prefer.

If we made a living on the island selling lemonade, it would take a long time before the dropped coconuts affected our earnings because we can’t control where, when, and how the dropped coconuts will be spent, nor who will spend them.

Since the richest 0.0001% can only drink so much lemonade and they collected the most dropped coconuts, it will take even more time for those dropped coconuts to affect our earnings.

This means it will take a long time before we can increase wages for our island employees, if at all.

So what’s the result of all of these dropped coconuts in our real world scenario?

Here’s a look at the rising average cost of goods against wages in US dollars, in nominal terms.

In the last 50 years, the price of oil has gone up 32x; housing 18x; pack of gum 20x; subway ride 16x; and movie night for two 15x.

The average annual and minimum wage increase? Eight times.

Welcome to modern slavery.

Enjoy saving your coconuts.

Be sure to share this with everyone.

The Equedia Letter

The Fed and government are brain washing the public that deflation is bad for the public but it is bad for people in debt like the government. Inflation is a tax on people with cash and allows the debtor to pay back with cheaper dollars.

Anyone who reads the history of the Fed understands the central banks make the living on debt – bring on the wars, etc.

Yea the US minimum was still $1.00/hr, Gas was 25-35 cents/gal, a new VW bug $1300, As 2nd Lt USMC I was paid $248+ $56 food allowance/ Month, coke cola $.25, at the O club beer $.25, Average starting pay A&S degree $400-500/month. Stamp US 4cents. When it comes to commodity type necessities. Their price increase approximates the increase in the minimum wage. There are exceptions.

When I went to grade school in the 40s occasionally my mother would treat my brother and I with a nickel with which we each got a fresh sweet roll at the bakery.

IN MY COLLEGE YEARS OF 1952-1956 EACH YEAR’S COST OF TUITION at Columbia College was $750 (that did not include room and board as I commuted from Brooklyn and the cost of a one way subway ride was 15 cents).

One year later, my Brand New 1957 Turquois and Ivory Chevrolet Bel-Air with anodized aluminum side panels and air conditioning cost $2425. When I got married in 1960, my parents bought a 1 bedroom coop in Brooklyn for themselves. The purchase price of the coop was $600.

Do you mean co-op? I keep my chickens in a coop. LoL

I = Inflation = increase in Currency supply

D = Deflation = decrease in Currency supply

$ = Dollar = unit of weight of silver (317.25g)

E = Eagle = unit of weight of gold

M Money= Gold /and/or silver

GDP = total of all goods and services of a country

+GDP = Economic growth = increasing GDP

-GDP = Economic contraction = decreasing GDP

S = Saving = delayed consumption

T = Time

x = Price

Y = value

You just sent out a fine 1/2 correct explanation that

begins to explain WHY the price of things increases over

time (Variable x) in a twenty variable equation.

Without defining any of the variables

To explain the economy to someone utilizing words that have

no fixed definition is like defining the economy in units of feathers. Or worse yet going to a weight loss clinic where the value of the pound changes each day. How do you have any idea if you are loosing or gaining weight?

What world or timeframe are you living on?

$ = Dollar = unit of weight of silver (317.25g)

Tom, your explanation of variables is the stupidest thing I have ever seen. Dollar does not equal silver and deflation does not mean a decrease in the money supply.

I normally bite my tongue when I see stupid comments from people who believe they are smart, but this comment, Tom, was utterly useless.

The posts talks about inflation and the Fed’s currency – not the economy. What were you reading, brainiac?

Bring on the coconuts and watch out for the helicopters!

Love the coconut illustration as it makes pretty clear the difference between monetary inflation which is a result of a debased currency because of too much central bank printing vs supply or demand induced price increases with a stable amount of currency.

The takeaway from all this is that even with all the productivity gains over the last few decades, standards of living have little to show for it.

Where did that ‘dividend’ from those decades of productivity growth go to? Hmmm, the bankers and those closest to the monetary spigots?

Of course, we now have a lot more debt and unfunded liabilities that are likely to be dealt with in the same way so lots more monetary debasement to come….even if the unfunded liabilities reneged upon.

Can they debase the coconuts before loading on the helicopter(s)?

Wonderful letter. You don’t really think about this in these terms very often. I remember having a conversation with an older coworker who was nearing retirement as few years ago. He was the first person to bring to my attention the extreme discrepancy in the increase in the price of goods and services and wages. I remember him telling me that wages haven’t kept up with the price of things. We are tradesmen so you would think the wages of the people who build and maintain the economy would correlate rather well with the increase in goods. But he remembered exactly what he made in wages back when he bought his first house. And it was something like 2-3 times your annual salary for a standard home. When we had the conversation I think it was closer to 5-6 times. It was basically the same idea with cars and some other items. I would assume it is no better now and likely far worse.

I guess the question would be, what can you do about it? I assume the answer is nothing really. The people in control of the system have lost touch with reality, and the only course of action is to keep the game going as long as possible. Because the alternative is likely a lot of pain for a lot of people for many years. It will take a long time to unwind the mess that has been created. I believe the US is the biggest perpetrator of this, and I believe some countries have had enough. I think Russia and China are leading the charge to dethrone the US. Question is how much is that going to hurt…..

If I know I can buy something cheaper in the future, I won’t buy it until I absolutely have to. If housing prices are deflating, who in their right mind would ever buy a house!

Credit underlies consumer spending and business investment. If my debts become more expensive in the future, I would never borrow money for anything. If I owned a business, I would invest only from cash on hand.

Deflation has the potential to bring an economy to a standstill.

Contrary to what you may believe about housing deflation, here in Vancouver, BC, when the housing prices dropped (deflated) after 2008, demand actually increased and caused another increase in construction etc. because housing became more affordable.

You are correct that credit can underlie consumer spending, but don’t forget, credit is what caused the financial crisis to happen just five years ago. Credit is good, but too much credit is extremely horrible.

All here is well said however complicated to some. Lets keep it simple.

In nature there is an opposite to everything. So for inflation there is Deflation. And what is deflating is what I call the black hand. The hand that keeps on robbing all of us of real value.

INFLATION; serves only the banking lords for so doing they make sure that we keep on borrowing. The higher the prices the more we live in debt to their system

Example: the first house I bought in Toronto cost me 55k 1981. same house today nothing much added cost now 600k

Now you know why the FED demands and places policy on countries to achieve a certain inflation number. This is for their own survival.

DEFLATION; what is depreciating another words if inflation means values go up then What is going down. The currency value is what is going down or being deflated. Interesting is how this phenomena is well hidden from everyday thinking.

Do I really need to live on a home that is value 600K after all not much has changed on the home.

WORST OF ALL; is that north America currency is at 90% devalued (deflated) so what happens when we get to 100% devaluation..The FED then takes over all the assets of a nation as it is bankrupt.

ENSLAVING FURTHER ALL CITIZENS FOR GENERATIONS

ALLAN; YOU SHOULD LOOK INTO THE BANKRUPTCY LAWS IMPOSED BY THE BANKERS ON NATIONS and add education to your followers.

Inflation is just the “hidden” tax,that makes up for the amount regular taxes don’t cover govt spending.So many people are ignorant and don’t understand economics,so politicians use the inflation tax,rather than regular taxes,that people would notice.So,you can’t get something for nothing,no matter what Obama Claus and other politicians promise.

I still haven’t figured out the “Reverse Coconut” scam. Reverse mortgage offers abound and I fail to see the bankers advantage.