There is one absolute certainty when it comes to our future: we need more resources and commodities.

That means – while unpopular with the new and younger generation of retail investors – mining (and mining stocks) will be critical in the world’s development.

The problem is that most investors have no clue what mining is, how to value junior explorers, and what to look for when investing in mining companies.

This problem is further intensified because mining itself is already an extremely risky business.

And one of the biggest risks in the mining industry is exploring for and defining an economic resource on which a mining project can be built.

That’s because most risk capital is lost in the ground.

A study by Mackenzie and Bilodeau (1984) found that in the period from 1955 to 1978 a total of $1.6 billion had been spent on exploration (excluding oil and gas) with thousands of mineral occurrences discovered. However, only 43 of these discoveries were considered to be economic, with even fewer ultimately being developed.

On average, it costs $38 million (1984 dollars) to find just one deposit during that time. In today’s dollars, that’s over $115 million!

And despite new technologies, finding new deposits (especially high grade) is harder today than ever before; most of the big deposits have already been found.

But that’s not all.

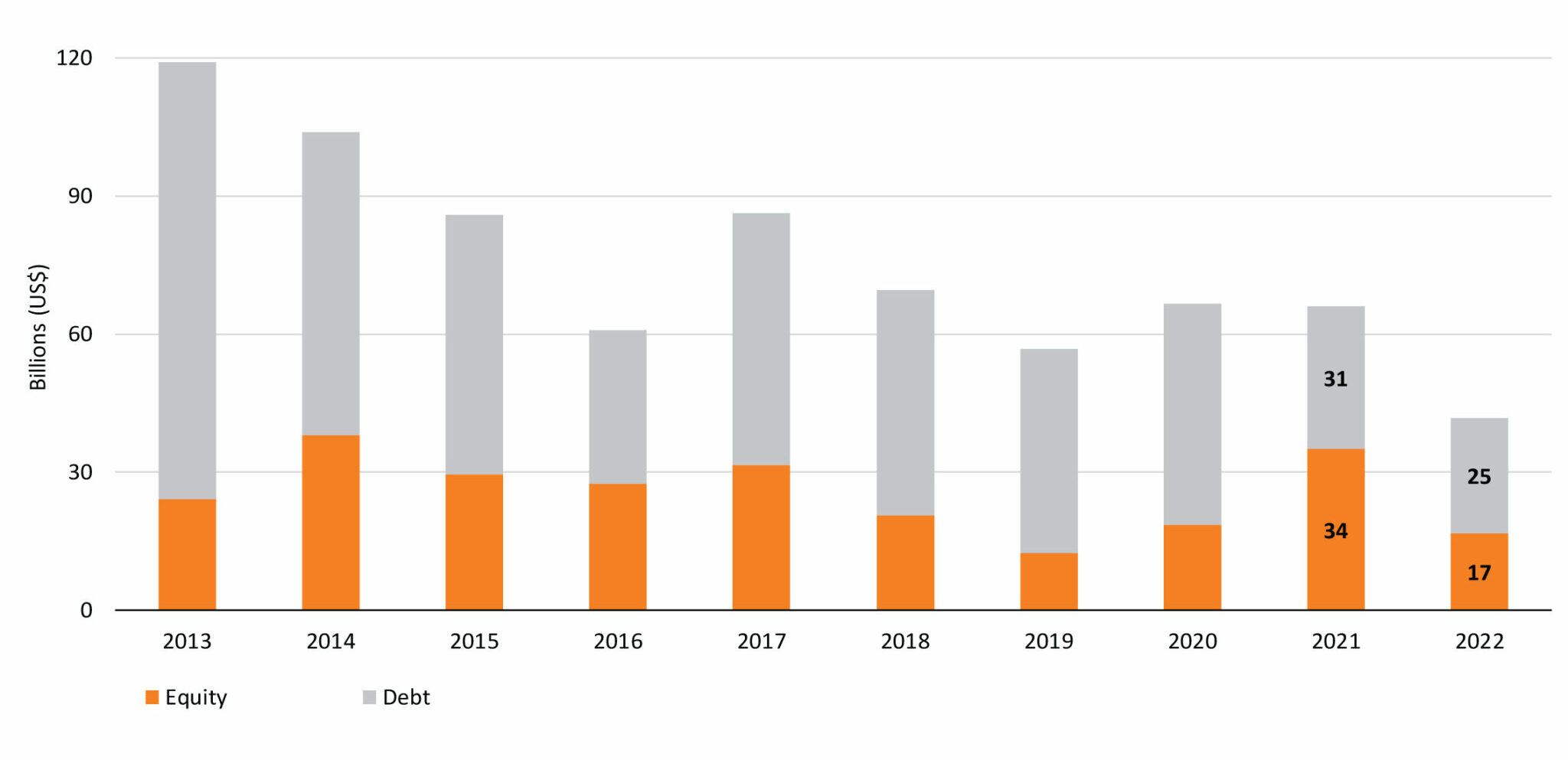

According to PDAC data sourced from S&P Global Market Intelligence, TMX Group and Natural Resources Canada (NRCan), in 2022, the mineral industry experienced a significant decrease in both equity and debt investments, collectively down 35% lower compared to the previous year.

This downtrend has lasted over a decade. Take a look:

The United States is home to biggest stock exchanges in the world and a global source of liquidity. But in 2022, funds raised on US stock exchanges for mining deals experienced a nearly 90% year-over-year drop. While 2021 was a big year for US funds raised for mining, around 40% of the total funds raised (US$3.6 billion) were allocated to critical minerals and lithium projects – and more than 75% of these funds can be traced back to just six specific deals.

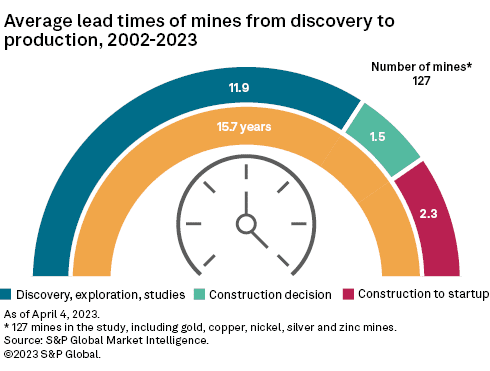

In other words, not enough money is flowing into the mining sector. Furthermore, according to an S&P report last year, it takes nearly 16 years to put a mine into production once a discovery is made – that’s based on info from 127 mines.

Via S&P Global:

“We calculated the average lead time for 127 precious and base metals mines that began production between 2002 and 2023 and were discovered from 1980 onward.

The 127 included mines have an average lead time of 15.7 years from discovery to commercial production, with a range of six to 32 years.”

If this keeps up, the price of EVERYTHING will go higher.

As a result, there will be a time when the younger generation realizes this and turns to mining stocks as their next big sector play.

And when that happens, you should be ready to make the right decisions based on a better understanding of how to value mining and mining exploration stocks.

But how do you know what projects are good enough for your investment?

The majority of us aren’t geologists, so for us to completely interpret or truly understand everything in an NI 43-101* report is difficult.

*more on this in a bit.

Even today, the majority of geologists have a hard time putting a resource together or moving a project from a resource to the feasibility stage. It takes some very special people in this industry to know where to drill and it takes even more special people to know how to put it together.

So while we’ll never learn everything, it certainly helps to learn the basics. Over the next few months, I’ll go into more detail on how to read 43-101’s, how to assess certain projects, and how to understand drill results.

For now, let’s get started with the basics.

Mining 101: Mining Methods

There are many methods of mining but the one most widely used thus far has been open pit mining. It accounts for more than 80% of mines in the United States.

Open pit/cast/cut or surface mining is a method of extracting ore or mineralization that is found very close to the surface, with a sufficient quantity of ore within a close proximity to make it economically viable to extract.

Think of it as digging a large hole in the ground.

Depending on the geometry and depth of the ore body, open pit mining is generally by far the most economical method of extraction for the recovery of low grade (1 g/t up to around 3-4 g/t for gold) finely disseminated ore. Ore is simply the naturally occurring concentration of minerals.

The advantage of open pit mining, as opposed to underground, is that it is usually easier, cheaper, and quicker to bring into production but generally relies on a larger resource base due to economical and social reasons. You’re digging a big hole in the ground – it better be worth it.

For example, underground gold mines usually require at least 4-10g/t (grams per tonne) of gold to be considered economically viable (dependant on a lot of factors such as country of origin, geophysical locations, and price.)

Cut-Off Grade

If you have invested in any mining company before, you will have heard the term cut-off grade.

Cut-off grade is the minimum metal grade at which a tonne of rock can be processed on an economic basis and determines the workable tonnage of an ore.

In Canada, resource calculations under the NI43-101 standard* will always include the cut-off grade.

*National Instrument 43-101 is a set of Canadian regulations and guidelines for the disclosure of information related to mineral properties. These regulations are enforced by the Canadian Securities Administrators (CSA) and are designed to ensure that investors receive accurate and reliable information when evaluating mineral exploration and mining projects in Canada. NI 43-101 establishes standards for reporting on exploration results, mineral resources, and mineral reserves, including requirements for qualified persons to oversee technical reports and assessments related to mineral properties. Compliance with NI 43-101 is essential for companies involved in the Canadian mineral exploration and mining industry, particularly those listed on Canadian stock exchanges.

Companies determine what it costs per ton of material mined and what the ore values is going to be from that tonne. From this, they can determine how much each ounce of gold will cost to mine. For example, in South Africa, the average all-in sustaining cost (the cost to mine) for gold mining is around $1,358 per ounce of gold. At today’s current gold price, that is a very profitable operation – and a reason why companies in this region can do really well as the price of gold climbs.

However, even with a strong resource, you still have to factor in the size of the mine and what it costs to put the mine into production. Even if you have a small resource that costs less than $1400/oz to mine, there is a great chance that financiers may not find the project large enough for their appetite, and thus the mine will not go into production – even at today’s high gold price environment.

Let’s not forget that you still need approval from the government to proceed. They won’t let you pollute their land and water without adequate and substantial economic benefit.

In short, a mine that appears feasible by the numbers may still not go into production – so don’t expect every company with a promising NI 43-101 resource to get there.

Before full on production can take place, there are many costly steps involved with bringing a mine into production, even if it is open pit. You have to identify the resource through various sampling methods, determine cut-off grades, and conduct a full-on feasibility study before you can even come close to production.

Some key points to focus on (in most cases) include:

- High Grade Levels – the higher the grade level of ore, the better the project

- Cut-Off Grades, Low vs. High – Cut-off grades are essential to determining the economic feasibility and mine life of a project. Increased cut-off grades can reduce political risks by ensuring higher financial returns over a shorter period of time. Conversely, lower cut-off grades may increase project life with longer economic benefits to shareholders, employees, and local communities. In short, a low cut-off grade does not mean a poor project.

- Easy Access – having easy access to infrastructure including water, electricity, and work force cuts down project costs significantly

- Proximity to Producing Mines – the closer the proximity to a producer, the less the infrastructure costs may be

- Indicated and Inferred in NI 43-101’s – Indicated estimate has a higher confidence level that such resources exists by estimating from sampling at places spaced closely enough that its continuity can be reasonably assumed. Inferred estimate is an estimate of resource whose size and grade have been estimated mainly or wholly from limited sampling data, assuming that the mineralized body is continuous and thus less confidence is placed on the data

- Never Rely on Estimates Alone – both indicated and inferred resource estimates in NI 43-101’s DOES NOT factor in the feasibility of its resources

- Place of Operation – a great resource is one thing, but a resource located in an unstable country with an unstable government can spell disaster

- Access to Capital – a well funded company usually means other professionals not only have done their research but believe in the project

- Great Management Team – a project can be great but ultimately, a management has to be able to execute

Mineable mineral deposits are rare and to bring a deposit into profitable production is even more so. The chances of bringing a raw prospect into production have been estimated at one in 5,000 to 10,000. That’s why there are many instances in which mining companies have revived old prospects and drilled just one more time before a discovery was made.

The great news is that with recent technological advances and the continual growth of resource prices, many projects with low grade ores and past producers are now becoming more economically viable.

Yet, few mining companies have the financial resources to delineate ore reserves too far into the future, which is why the big guns, such as Barrick, continually seek out and invest in other gold juniors to increase their reserves. This is yet another reason why a junior with a nearby producer has a much higher chance of going into production because the costs of production are often too high for a junior to fund by themselves. Economies of scale is a big asset in the mining industry; the ability to use someone else’s tailings dam or processing mill can save a junior millions.

Feasibility Studies

There is a common misconception surrounding feasibility studies. We know they’re important but their significance is commonly misconstrued. Make one mistake or skip one step of the process and it can have detrimental effects on a mining project.

A mining feasibility study, in short, is an evaluation of a proposed mining project to determine if the mineral resource can be mined economically. But there are many stages of this process before the actual feasibility study or report is finalized.

First off, there are three main feasibility studies: the scoping study, preliminary feasibility and detailed feasibility.

The first one is the order of magnitude, conceptual or what we investors generally call it, a scoping study or Preliminary Economic Assessment (PEA).

Scoping Study or PEA

This first step in the feasibility process is the initial financial appraisal of an indicated mineral resource. This study usually begins once a sufficient level of drilling and sampling to define a resource has been completed, such as a NI 43-101 in Canada. Scoping studies are developed by copying plans and factoring known costs from industry standards and comparable historical data.

It involves a preliminary mine plan, and is the basis for determining whether or not to proceed with an exploration program, and more detailed engineering work.

The end result of the study is a description of the general features and parameters of the project and an order of magnitude estimate of capital and operating costs. A study of this level is valid to determine whether a project is worth pursuing further but not enough data has been collected for reserve definition. This study is generally 35 -50% accurate.

Don’t mistake the term mineral reserves for mineral resources.

Mineral resource is a guess of what’s in the ground such as the indicated and inferred resources found in NI 43-101’s. Mineral reserve, on the other hand, is the resource known to be economically feasible for extraction. Few projects survive this part of the study.

The next stage after this is the preliminary feasibility study or “prefeasibility study.”

Prefeasibility Study

This study determines the mining and milling extraction methods and rates, the product recoveries, environmental and permitting issues, and preliminary capital and operating cost estimates. It also determines whether or not to proceed with a detailed feasibility study, which is very costly.

As part of this process, areas of concern that need further research during the feasibility stage need to be identified. These areas often include geotechnical studies for mine, waste dumps, and tailings facilities design, metallurgical testing for refining estimates of product recoveries, and waste characterization studies. Identifying these items at this stage can avoid costly delays during the feasibility stage – any additional delays and costs can be detrimental to a project which often translates to shareholders directly. Added costs mean further funding may be required and could add further dilution to shareholders.

Depending upon the level of detail in these studies, and the securities exchange that is involved, reserves can, in some cases, be declared at this point.

This preliminary feasibility study is usually 20-30% accurate and only 50% of the companies that go through this stage pass onto the final stage of the feasibility study or what many call the “bankable” study.

Bankable Feasibility

Detailed or “bankable” feasibility studies are the most detailed and usually determines whether or not to proceed with the project. General industry standards of this study results in estimates that are within 15 percent accurate.

In essence, this stage is simply a refinement of the pre-feasibility study, which evolved from the scoping study. Key components in the feasibility study are the mine design, production schedule, a detailed process flow sheet, product recoveries, a detailed plant design, consideration of the environmental issues, detailed capital and operating costs estimates, and an economic model of the project. Each of these components is EXTREMELY important.

If a company can make it this far and is feasible after this stage, they can generally take this study to the “bank” for financing purposes.

At this point there is sufficient information to declare reserves, provided the project has positive economics and is noted as bankable. However investors always seem to forget that “bankable” describes only the level of accuracy of the analysis and not necessarily the outcome of the project.

As I said, just because a project is feasible, doesn’t mean it will get the go ahead for production. Just because a feasible project can make money, the return on investment may not be enough for the company to advance the project – or the risk too high for such reward.

For example, the profit from the mine may be $100 million but it may cost $95 million to build it out. So is it feasible? Yes. But does it make sense to spend $100 million to make $5 million – with many risks involved? I doubt it.

If the benefits do not significantly outweigh the costs, not only may the government deny you permits, but your financiers may pull out.

At this feasibility level, roughly 20% of the companies will fail, and of these, most fail as a result of either overly optimistic assumptions or skipped steps.

For this step to be successful, the scoping study and the pre-feasibility study must be conducted at reasonable estimates; many companies will conduct more than one scoping study to ensure the accuracy of the data.

I have seen companies shell out a lot more cash and time than they needed to once they hit this stage because they over emphasized their scoping and pre-feasibility studies.

A great emphasis needs to be placed on each and every step with new rules and regulations constantly changing the way feasibilities are done (welcome to the world of regulation).

While much of what I covered this week seems simple, it is imperative that investors in the mining sector have a basic concept of why they’re investing in certain companies.

While buying majors can be bountiful during times of rising commodity prices, the same cannot be said about investing in juniors – especially not in this market.

In this market, capital will be fuelled into projects that have a high hope of success – not just a play on some overly promoted drill results. That’s why you may see the price of gold go up, yet the price of your gold junior still lags. But eventually that will change.

Over the coming weeks, we’ll go into more depth and discussion surrounding mining valuation and potentially presenting new ideas to play with.

Seek the truth and be prepared,

Carlisle Kane

Forward-Looking Statements

This Newsletter and report contains certain forward-looking statements that may involve a number of risks and uncertainties. Actual events or results could differ materially from current expectations and projections. Except for statements of historical fact relating to the project, certain information contained herein constitutes “forward-looking statements”. Forward-looking statements are frequently characterized by words such as “plan”, “expect”, “project”, “intend”, “believe”, “anticipate” and other similar words, or statements that certain events or conditions “may” or “will” occur.

Except for the statements of historical fact, the information contained herein is of a forward-looking nature. Such forward-looking information involves known and unknown risks, uncertainties and other factors which may cause the actual results, performance or achievement of the Company to be materially different from any future results, performance or achievements expressed or implied by statements containing forward-looking information.

Although the Company has attempted to identify important factors that could cause actual results to differ materially, there may be other factors that cause results not to be as anticipated, estimated or intended. There can be no assurance that statements containing forward looking information will prove to be accurate as actual results and future events could differ materially from those anticipated in such statements. Accordingly, readers should not place undue reliance on statements containing forward looking information. Readers should review the risk factors set out in the Company’s prospectus and the documents incorporated by reference.

Cautionary Note to U.S. Investors Concerning Estimates of Inferred Resources

This presentation uses the term “Inferred Resources”. U.S. investors are advised that while this term is recognized and required by Canadian regulations, the Securities and Exchange Commission does not recognize it. “Inferred Resources” have a great amount of uncertainty as to their existence, and great uncertainty as to their economic and legal feasibility. It cannot be assumed that all or any part of an Inferred Resource will ever be upgraded to a higher category. Under Canadian rules, estimates of “Inferred Resources” may not form the basis of feasibility or other economic studies. U.S. investors are also cautioned not to assume that all or any part of an “Inferred Mineral Resource” exists, or is economically or legally mineable.

Disclaimer and Disclosure

Disclaimer and Disclosure Equedia.com & Equedia Network Corporation bears no liability for losses and/or damages arising from the use of this newsletter or any third party content provided herein. Equedia.com is an online financial newsletter owned by Equedia Network Corporation. We are focused on researching small-cap and large-cap public companies. Our past performance does not guarantee future results. Information in this report has been obtained from sources considered to be reliable, but we do not guarantee that it is accurate or complete. This material is not an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy any securities or commodities.

Furthermore, to keep our reports and newsletters FREE, from time to time we may publish paid advertisements from third parties and sponsored companies. We are also compensated to perform research on specific companies and often act as consultants to many of the companies mentioned in this letter and on our website at equedia.com. We also make direct investments into many of these companies and own shares and/or options in them. Therefore, information should not be construed as unbiased. Each contract varies in duration, services performed and compensation received.

Equedia.com is not responsible for any claims made by any of the mentioned companies or third party content providers. You should independently investigate and fully understand all risks before investing. We are not a registered broker-dealer or financial advisor. Before investing in any securities, you should consult with your financial advisor and a registered broker-dealer. The information and data in this report were obtained from sources considered reliable. Their accuracy or completeness is not guaranteed and the giving of the same is not to be deemed as an offer or solicitation on our part with respect to the sale or purchase of any securities or commodities. Any decision to purchase or sell as a result of the opinions expressed in this report OR ON Equedia.com will be the full responsibility of the person authorizing such transaction.

Again, this process allows us to continue publishing high-quality investment ideas at no cost to you whatsoever. If you ever have any questions or concerns about our business or publications, we encourage you to contact us at the email or phone number below.

Our views and opinions regarding the companies within Equedia.com are our own views and are based on information that we have received, which we assumed to be reliable. We do not guarantee that any of the companies will perform as we expect, and any comparisons we have made to other companies may not be valid or come into effect. Equedia.com is paid editorial fees for its writing and the dissemination of material and the companies featured do not have to meet any specific financial criteria. The companies represented by Equedia.com are typically development-stage companies that pose a much higher risk to investors. When investing in speculative stocks of this nature, it is possible to lose your entire investment over time. Statements included in this newsletter may contain forward looking statements, including the Company’s intentions, forecasts, plans or other matters that haven’t yet occurred. Such statements involve a number of risks and uncertainties. Further information on potential factors that may affect, delay or prevent such forward looking statements from coming to fruition can be found in their specific Financial reports.

Equedia Network Corporation is also a distributor (and not a publisher) of content supplied by third parties and Subscribers. Accordingly, Equedia Network Corporation has no more editorial control over such content than does a public library, bookstore, or newsstand. Any opinions, advice, statements, services, offers, or other information or content expressed or made available by third parties, including information providers, Subscribers or any other user of the Equedia Network Corporation Network of Sites, are those of the respective author(s) or distributor(s) and not of Equedia Network Corporation. Neither Equedia Network Corporation nor any third-party provider of information guarantees the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any content, nor its merchantability or fitness for any particular purpose.

One potentially major issue that is not addressed in this article is the potential timeline to permit any type of project, especially going from prospect to mine, even once a bankable feasibility study has been completed. In some jurisdictions it is as little as two years, while in others it may be 7-10 years or more. And in that time frame governments can change, rules and regulations can change, and commodity prices can change.

Another problem that exploration and mining companies have now is NGOs, which can stir up opposition from the local population and local (and even national) governments, making it even more difficult in some regions to do any mining.

The original intent of the 43-101 report was to let non-technical people understand the information about a property so they can make an informed investment decision. It meant presenting information at a level that did not require extensive expertise or knowledge about geology, mining, economics, etc. Over time the 43-101 report has evolved into a very technical document that is almost impossible to understand even for knowledgeable people such as geologists. Gone are the days when the sole author was the qualified person; instead we rely on specialists to write their own sections in the report. Unfortunately not all of us know how to write to be able to convey ideas/concepts that is understandable for non-technical readers; it’s a skill that is rarely taught as we become geologists, geophysicists, geochemists, modelers, etc. who are involved in creating a 43-101 report.

Thanks for the info.

I actually invested some money into one of the stocks you protomted and pumped up; ABZU and it’s now worthless………. I didn’t invest enough to cry about it; so not crying here.

That being said, yes, I understood the risks and your disclaimers. At the same time, Once bitten, twice shy…